Developing and defending a new product business case can be an intimidating task for many product managers. Let’s start with two common myths.

Myth One: The more a precise business case is, the more accurate it is.

Ironically, this is not true. Business cases rely on assumptions and estimates about the future: forecasted sales, customer intent, and expected costs. Adding more decimal points may provide the appearance of precision, but the reality is there is still a lot of subjectivity to the numbers.

Myth Two: A successful business case always gets funded.

A successful business case is one that helps make the right decisions. Keep in mind that the purpose of the business case is to determine the business potential for a product concept. Or it might be to determine what changes are necessary. But some product managers believe they HAVE to get approval. As a result, they are tempted to pad projections or become wildly optimistic on their assumptions. On the other hand, if they presents realistic data and truly believes in the value of the proposed product, it defines a successful business case and should be funded.

Definition of Business Case

What exactly is a business case? I define it as a structured proposal for investment in a new product. It will contain:

- market requirements (i.e., needs or benefits)

- general statement of the feasibility of building a product that addresses the requirements

- discussion of the size of the opportunity

- financial overview

- resources required to address assumptions and risks

In other words, it provides the case (i.e., rationale) to support economic investment in the new product project. It may also suggest contingency plans if the assumptions become invalidated.

What’s the REAL Purpose of a Business Case?

The goal is to provide ammunition for decision-making. It should explain why other concepts were rejected in favor of this one.

Start with gathering data on market potential. Assess what factors increase or decrease potential market acceptance, and then forecast accordingly. The business case should predict the outcome if this decision is taken. Determine reasonable cash flow projections with rough probabilities of achieving various cash flows during an acceptable payback period.

Include Soft Benefits

Beyond the forecasted revenues and costs, there may be soft benefits to consider. These could include increased brand awareness, referrals, or higher customer satisfaction. For example, if the assumption is that a new product will prevent defection to the competition, the financial value of this business can be estimated.

Remember, This is a Proposal

The business case is a skeleton plan that provides the financial, competitive and market justification for the project. It is essentially an economic proposal for an investment, and should build from data. Think of a business case in the context of an entrepreneur compiling a business plan in an effort to get venture capital, or a loan from a bank. But in this case, the company is the “bank.”

Answer these questions. Why are you considering this concept at this time? Consider its fit with the business strategy, product strategy, and/or product roadmap. Is this a proactive or reactive product? Will it fill a gap or open new opportunities? What is the size of the opportunity and the expected financial performance? Is the concept manufacturable, and do we have the capabilities to do it? What might be the consequences of NOT pursuing this concept? What are the risks and how will they be mitigated? Don’t assume the answers to all of these questions are obvious. They might not be.

Components of the Business Case

Companies will require different content for a business case depending on the type of industry or product and on the needs of the individual business

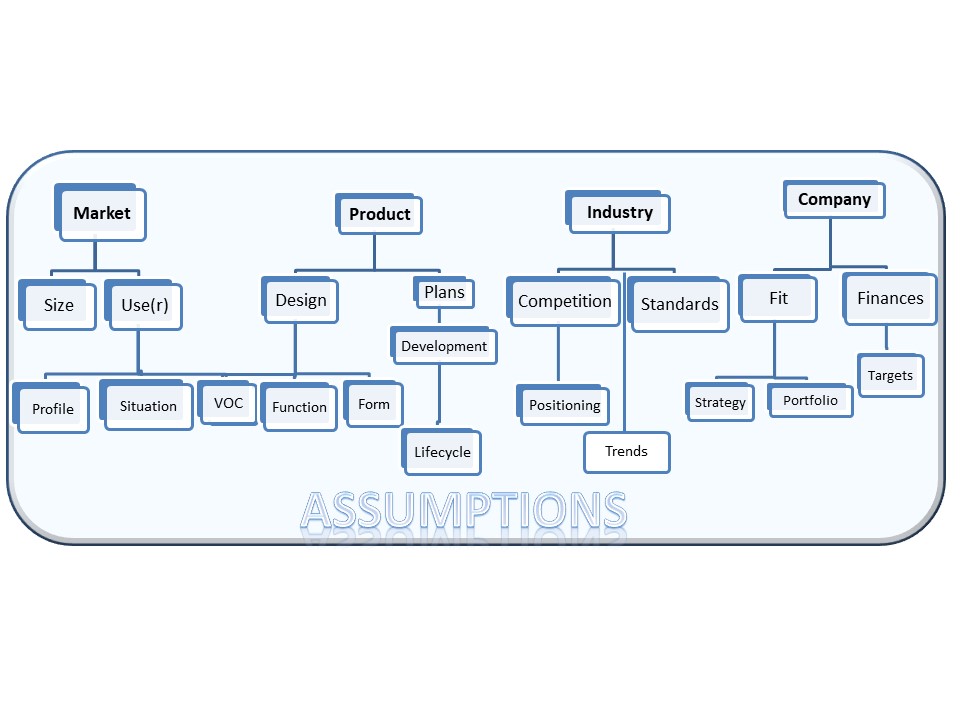

The following figure lists the primary components and sub-components of a business case. Note that underlying all of them are your assumptions. Clearly state important assumptions and “pressure test” them against other people’s perspectives. What would happen to the outcome if these assumptions changed? Look at best- and worst-case scenarios. Challenge yourself as you examine your beliefs about each component of the business case.

Framing and selling the business case

Assuming you truly believe in the proposed product concept, the business case should persuade management to pursue it. In other words, the information should be presented in a way that informs and encourages an affirmative “vote.”

The product manager may need to make a formal presentation of the idea to management. In that case, it’s important to identify the “hot buttons” of each person prior to the meeting and come prepared to address them. Top management will be interested in the return (expressed by NPV or IRR) and payback. Sales executives will want to know the strengths of the product as compared with the competition. Operations executives will be concerned about design complexity and manufacturability.

Consequently, the product manager has to be prepared to address specific functional concerns in addition to providing a general overview. The most important factor in disarming adversaries is to get their involvement and buy-in prior to the final review. Marty Schmidt suggests specific approaches to these problems in his blog post, Your Business Case Critic: How to De-Claw the Cat.

Further information

Perhaps the most comprehensive source of information on building business cases is Marty Schmidt’s Business Case Analysis website. It provides a useful blog, along with links to Business Case Essentials (2018), Business Case Templates (2019), and The Business Case Guide (2018).